Ariana Rodriguez | Contributing Writer

The first language I ever learned to speak was Spanish. Speaking my family’s mother tongue is something that is second nature to me. It is something I am very grateful for and value wholeheartedly, especially in this day in age when being able to speak more than one language is considered an asset.

Recently, though, I’ve come into contact with people who don’t feel the same way. They have tried to censor my ability to speak Spanish openly. At one point, I too, spoke only one language, so I can sympathize with people who don’t understand more than one language, but only to a certain extent. It is because they have tried to silence something that is so deeply rooted in my being that I can’t sympathize with their attempt to violate my First Amendment right regarding the freedom of speech, nor do I appreciate feeling harassed and reprimanded for speaking my first language with my peers.

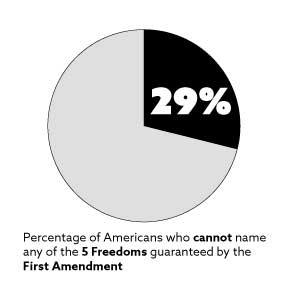

Dealing with this personal issue led me to become more aware of the five freedoms guaranteed to me by the First Amendment, something that surprisingly 29% of America cannot name at all (The State of the First Amendment Survey: 2014). It also led me to become aware of much larger issues that could potentially silence a significant part of America: the “English Only” movement and its effort to establish an official national language.

The push for a national language is not a new development. It’s an issue that dates far back in time as The Declaration of Independence itself. According to Dennis Baron, professor of English and Linguistics at the University of Illinois, one of its authors, President Benjamin Franklin, had a strong animosity toward German immigrants and their lack of proficiency in the English language. Instead of regarding bilingual signage as a learning tool, Franklin viewed signage displayed in both German and English as a threat to the American way. This was ultimately the beginning of the “English Only” campaign throughout history.

However, the modern resurgence of the “English Only” movement has emerged within the last 30 years. Many believe it grew largely in part because of political opposition to immigration issues. Its main objective is to declare English the national language in order for all government documents and communication to be presented solely in English. This would drastically limit resources available to those people who don’t understand English fluently and it would ostracize them from America more than they already are.

As the push for a national language continues, 31 states have passed statutes declaring an official state language, Iowa being one of them, when Rep. Steve King authored the measure in 2002. According to the Sioux City Journal from 2007, King opted to sue Secretary of State, Michael Mauro, and governor-elect, Chet Culver for not abiding by the Iowa English Language Reaffirmation Act when they displayed voter-registration materials in languages other than English. Later, in 2008, the Iowa District Court ruled that having these materials accessible in “foreign languages” was illegal (The Sioux City Journal). Imagine having to fill out a complicated form in a language you are not proficient in. Wouldn’t a copy in a language you understand assist you in filling out the form and also, help you learn and recognize terms you are not familiar with?

In 2005, a Kansas public school student was suspended from school because he was heard speaking a foreign language in the halls by a teacher (The Washington Post). First of all, this is a violation of civil rights, linguistic discrimination to be more exact, but what is considered foreign? The U.S. does not have an official language, but yet every other language that is not English is considered foreign. What about the languages spoken by Native Americans? Their languages cannot possibly be considered foreign, right? If the case argued was about what is considered foreign in the U.S., then wouldn’t English be at the top of the list when it comes to a foreign language?

Surely, Americans must think of this contradictory idea before they shout out, “English only, USA” during a crowded kindergarten music concert, right? Perhaps they understand the implications an official national language could have on dividing a nation that is already being torn apart by racial intolerance and cultural tension, but still choose to ignore it.

Yet, there is a question that has been digging at me since I personally experienced the silencing issue I mentioned before. Would speaking Spanish openly be less controversial if it wasn’t so closely associated with border control or immigration reform? Would I be able to speak my mother tongue freely without the fear of censorship or discrimination if it was instead Dutch, Swedish, or French? The truth of the matter is that I shouldn’t have to worry about what language I choose to speak. The First Amendment to the United States Constitution so declares:

Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the government for a redress of grievances.

Graphics by Ariana Rodriguez