Jonathan L. Ehrlich | Contributing Writer

This is the last week of classes of my undergraduate education. I came to BVU three years ago thinking I would be a scientist because I was wildly successful at general chemistry while at community college. After studying biology here for three semesters, I recognized that the doors of scientific knowledge were not opening as expected and the passion to keep pushing on them was fading.

After two consecutive semesters of academic failure, I was resigned to the idea that perhaps my peers were right to think that the purpose of college is to get it done and get a job. You see, I have never thought that the purpose of schooling was to get a degree and a job. I always thought that the purpose was to educate oneself in order to be a more capable human being. Failure shakes people’s convictions though, and I was no exception.

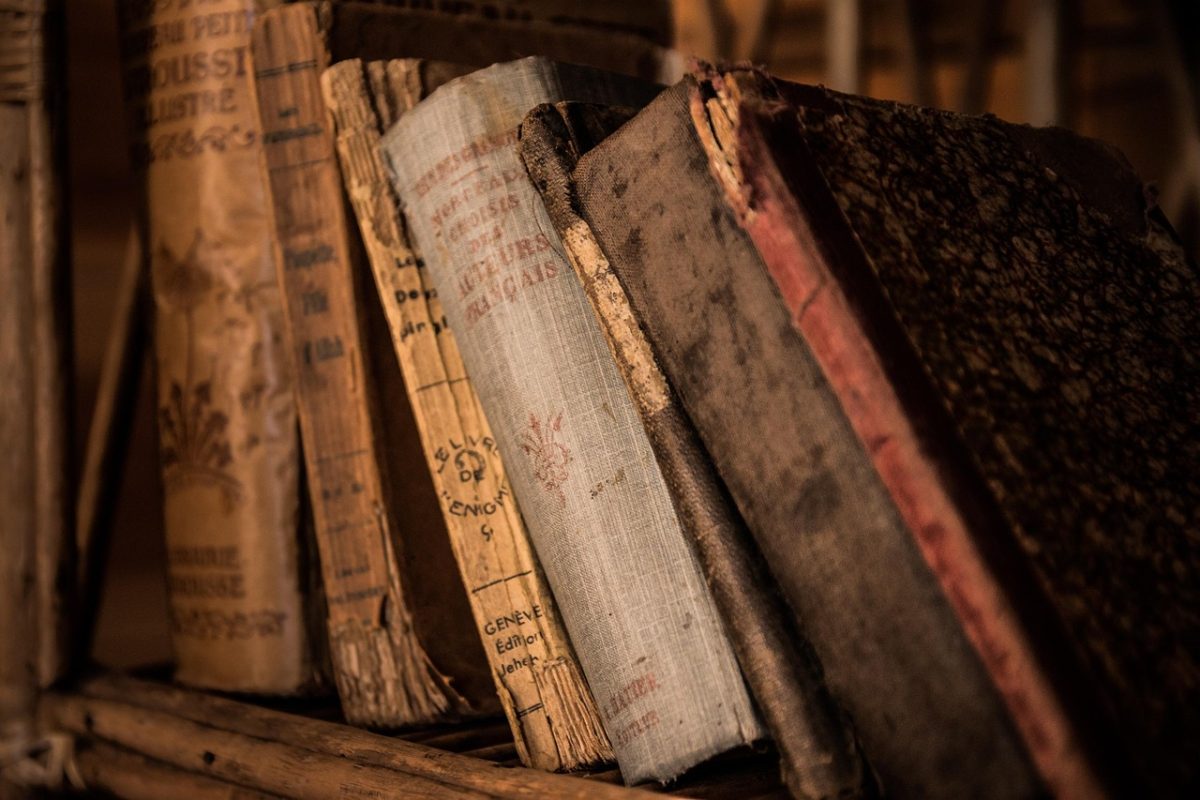

My doubts about purpose compelled me to search the academic catalogue for a different program. I found philosophy and religion and switched majors. As a philosophy and religion major I studied how and why to think. Doing so strengthened the entirety of my learning skills, and even revealed why I may not have been successful studying science (the reason was that I was looking to answer ‘why’ questions before learning the language of the discipline). I became obsessed with learning how to think, and remain so even now.

It seems that truly successful people in any field are, or were at one time, obsessed with their subject matter. Accomplished scholars, entrepreneurs, artists, and craftsman have to dedicate themselves fully to their disciplines in order to understand it to an uncommon extent. Philosophy and religion studies gave me a reason to obsess. In doing so it saved my future.

Had I decided that I was unfit for BVU because I failed in my first attempted undergraduate subject, I would not have kept pushing on the doors of knowledge. Given that I am writing this now, it is obvious that I did not judge myself unfit. Had I not found the philosophy and religion major, a discipline that is teaching me how and why to think rather than what to think, I would not have reformed my strategy for learning. Had I not reformed, I would not have taken the graduate and law school exams, done well, and been offered admission at multiple schools.

The point is this: Failure is not the end of learning; it is a part of learning. I encourage every student to push on the doors of knowledge as hard as he or she can. If it opens, go for it. If it doesn’t, go to a different door. This is one of the great lessons that can be learned at BVU when the student is willing and the different door exists.

Photo Courtesy of Flickr Creative Commons