COVID-19’s Effect on a D.C. Intern

March 24, 2020

Wednesday, Jan. 22: I boarded my 11 a.m. flight to Washington, D.C., with a one-way ticket from Omaha. I was nervous to head to the big city, but those nerves quickly turned into excitement for the adventure in store. Four months in the nation’s capital for an internship with the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars. It would be my first time seeing all the monuments, memorials, and museums, and who knew—maybe even my future job.

…

Wednesday, Mar. 11: The Washington Center, the internship program in Washington, D.C. that I’m participating in through Buena Vista University, sent an email to its students, informing us about the switch to online classes the following week, most likely for the remainder of the semester.

…

Thursday, Mar. 12: My supervisor called me into her office. When we were through meeting, she told me she was sorry that my internship experience has to be like this, and she wished she had a better alternative.

“I was going to say, ‘it’s okay, it happens,’ but it really doesn’t, does it?” I said to her.

“No, not really,” she replied. I left her office not knowing if I’d ever actually see her in person again.

…

Friday, Mar. 13: I woke up at 8:30 a.m., not wanting to leave my bed. My class wasn’t until 10:45. So, I laid there for at least an hour. I couldn’t really place the feeling I had, but it was a mixture of disappointment with a dash of indifference. Usually the last day of class calls for a celebration to reminisce (or forget) the past semester you’d finally completed. But this last day was different. It wasn’t supposed to be the last.

…

Saturday, Mar. 14: In just a few short days, the city had turned completely on its head.

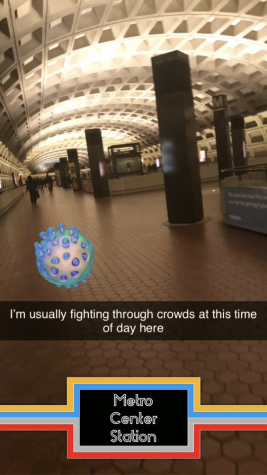

The scope of this world-wide panic attack just kept widening. When I originally received the Washington Center’s email, I was still in the boat of “This whole coronavirus thing is way overblown.” I snickered at the people who tried to stay six feet away from others; I rolled my eyes at those stockpiling for the apocalypse; and I even mentally thanked those who were too scared to take the metro, because I finally had room to breathe on my morning commute.

But before I knew it, work was moved to home. Museums and other attractions closed up shop. And churches called off weekend services. First, Muriel Bowser, the mayor of Washington D.C., announced a state of emergency (Mar. 11). Then the World Health Organization (WHO) declared a pandemic (Mar. 12). Next thing I knew, President Trump declared a national emergency (Mar. 13). All of a sudden, my easy dismissal of the warning lights seemed naïve.

The response to the growing concern made me feel like I was trapped on a train going at high speed with no stops in sight and no way off. After our final in-person class, my roommates and I began discussing what to pack into the weekend before everything closed for the next few weeks, but everything we looked up had already beat us to that point. All of a sudden, we were the protagonists zigzagging through a burning forest as flaming trees fell in our way no matter which direction we went. Every path was a dead end. There was no way out.

…

Monday, Mar. 16: It took less than a week for our entire country to practically shut down, and only a few days more to squeeze me out of the city. I decided to leave D.C. The decision broke my heart. I wasn’t at all ready to leave, but I felt I had no other choice. I had to go before domestic flights got canceled and I had no way back to my family.

…

Wednesday, Mar. 18: I’m home in Nebraska. It’s nice being with my family, but I can feel how this pandemic is affecting them, too. Usually, this stuff doesn’t matter in Midwest small towns; nothing happens here. We typically are far away from whatever is in the news. But viruses don’t care where you are from. My brother is back from college indefinitely, my sister is missing out on her senior prom, and my dad had to close down the lobby of his Arby’s store.

As I began my first day of teleworking from the kitchen counter, I looked out the window where the sun was glistening off the spring snow, and I couldn’t help but think that it was mocking the rising tension in my home.

…

Friday, Mar. 20: After reflecting on weeks that felt like years, I came to the conclusion that this virus is causing a lot more issues than just the three symptoms listed on the CDC’s website. For those of us with a history of anxiety and depression, it’s the catalyst for a downward spiral. Even for those without a history, terms like “quarantine,” “pandemic,” and “no toilet paper” in everyday conversation is enough to make anyone feel hopeless. My D.C. roommate admitted she hadn’t had this certain pain in her chest since working in politics, but it was back. Neither of us had any idea how a virus could cause this much stress.

While I haven’t yet been infected, I have been affected. I’m slated to graduate in May, and the unknown scares me. No one knows how long this will last, or what it will do to the job market, the economy, or the social fabric of our country.

But we have to have faith that the human race will find a way through this, just as it did in the days of 16th c. England “when the plague visited London almost every year or…a Viking age when raiders from Scandinavia might land and cut your throat any night,” C.S. Lewis reminds us.

In fact, if you read C.S. Lewis’ essay, “On Living in an Atomic Age,” and replace “atomic bomb” with “COVID-19,” you realize just how true his words ring for us today in our own “Coronavirus Age.” Lewis reminds us that while the exact circumstance we are going through is novel, the core of it is something we’ve already experienced many times – a threat to our survival. And we’ve made it through each time before.

…

1948: “The first action to be taken is to pull ourselves together. If we are all going to be destroyed by an atomic bomb, let that bomb when it comes find us doing sensible and human things—praying, working, teaching, reading, listening to music, bathing the children, playing tennis, chatting to our friends over a pint and a game of darts—not huddled together like frightened sheep and thinking about bombs. They may break our bodies (a microbe can do that) but they need not dominate our minds.” – C.S. Lewis