Reprinted with permission from The Storm Lake Times Pilot and author. Fifth story in a series.

I’ll be home for Christmas

You can plan on me…

Bing Crosby’s brand new, smash-hit song was likely one of the many Christmas songs echoing across the Buena Vista College campus in December 1943. Christmas festivities had begun on campus before the last rays of the November sun had even set, before the first cold December breeze had even slipped under the door.

Just a few days before Thanksgiving, campus fraternities began advertising their Christmas parties and the college began planning their Christmas services and holiday concerts. Christmas looked different this year, but Beavers were no less cheerful. “The merry mirth, tinkling bells, and elaborate decorations are absent from the expectation of the coming holidays,” The Tack editors published, “but the spirit that is prevalent in the hearts of the American people has not been stilled.”

Christmas 1943

Though the Christmas spirit remained, there was a palpable absence on campus. During the Christmas season of 1943, there were more Beavers away from home than ever. Two such Beavers were Gerald Holaday and Vernon Niebruegge Nelson.

It is hard to say whether Gerald and Vernon were ever friends, but it is almost certain that they knew one another. They were, after all, members of the same class, and BVC wasn’t a big campus. For an entire year, 1936-1937, they existed in one another’s orbits. They attended the same classes, walked the same sidewalks, perhaps even liked the same professors. Gerald was sporty and Vernon was studious, but they still would’ve found themselves in near constant proximity. In December 1943, though, they couldn’t have been further apart.

The Athlete and “The Brain of the Class”

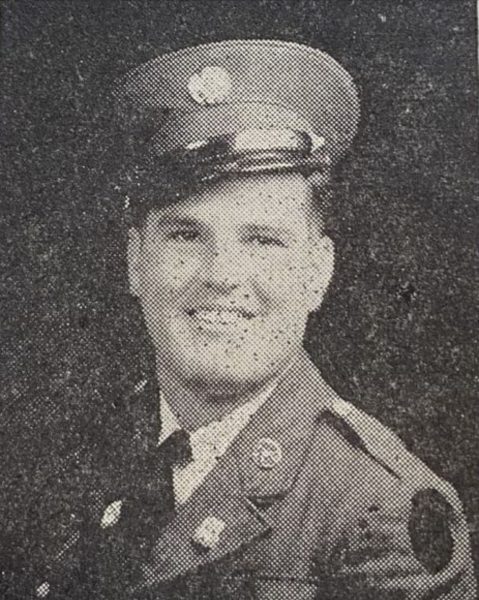

Gerald Holaday, originally from Greenfield, was a latecomer to college. By the time he attended his first semester in 1936, he was already 23 years old. What he did in the years before he started at BVC is hard to say but, given the Depression, he probably worked with his father on their farm. On the football field, he quickly distinguished himself as a talented player, winning a minor award after just one season. He was jovial and generous with a bright smile and dimpled cheeks. Even with his success, he only spent one year at BVC, returning home to work as a carpenter in late 1937 and joining the Iowa National Guard in 1941.

Vernon Nelson, from Schaller, started his first semester at the same time. He was a studious and kind young man, described by his friend Bob Meinhard as “the brain of our class and destined for a life of professional and personal success.” He also served as a Gospel Ambassador, traveling around with fellow students to speak at various programs. Even though his studies kept him busy, he still found time to get up to mischief with his friend and classmate Darrell Lindsey, once dressing in only diapers and hanging out around campus with Darrell and Dave Peterson as the “Three Bares.” Unlike Gerald, Vernon graduated in 1940 and almost immediately enlisted in the U.S. Naval Air Corps.

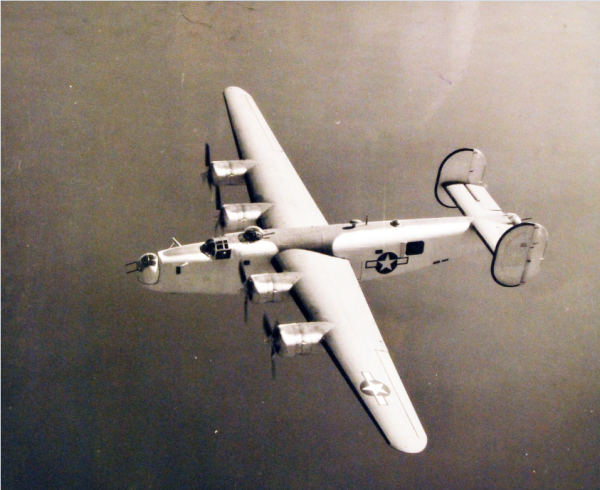

Although Vernon enlisted first, it was Gerald who went overseas first, departing the United States on May 1, 1942. Gerald spent his first Christmas abroad trudging through the Tunisian wilderness during Operation Torch with the 168th Infantry. Vernon spent Christmas of 1942 in Florida learning to pilot B-24 Liberators before transferring to San Diego and, in September 1943, being sent to a ship in the South Pacific from which he began flying missions.

“They Dreamed Not of Sugar Plums”

During the Christmas season of 1943, thousands of miles from home, Gerald and Vernon must have found it very difficult to keep their spirits up. People at home found it difficult, too, but they were hopeful. As published by The Tack editors: “it is impossible to celebrate as we have in other years, but we can still keep the spirit and look forward to another Christmas not blackened by the reality that faces us today. With new hope that bells may ring out in the crisp winter night and children may again dream undisturbed, we look to the new year.”

On such winter nights, 14,000 miles apart, perhaps they comforted themselves with thoughts of that new year, that new world, that place where snow and mistletoe ruled the season. Perhaps, under their breaths, they hummed that same Bing Crosby song as their classmates back at BVC: I’ll be home for Christmas…

They dreamed not of sugar plums, but of a peaceful world. A world that they would never get to see.

“Greater Love Hath No Man”

In the late days of November, Gerald and the 168th entered combat in the Italian mountains. They were given the order to seize Mount Pantano, a knobby 4,000 foot mountain some one hundred miles from Rome. Combat was brutal. The weather was freezing and muddy and the troops lacked proper winter gear. Supplies, which had to travel up winding, steep trails by mule, were hours away. Casualties had to be evacuated by foot down those same trails and under constant German fire. At one point, surrounded by casualties and cut off by mortar fire, the 168th resorted to drinking only rainwater. When they ran out of ammunition, they threw rocks and ration cans.

On December 2, in the middle of this horrible, WWI-esque warfare, Gerald and his unit were pinned down by machine gun fire. Cornered and desperate for a reprieve, the men of L Company soon realized that the only way to break free from their position was a sacrifice play: someone would have to throw a grenade into the German machine gun nest and, in doing so, expose themselves to the deadly maelstrom of lead. Will anyone volunteer? Their commander may have yelled. Yes, sir, Gerald may have answered.

Bullets whizzed overhead and splashed into the mud. A grenade smashed into the machine gun nest, killing the Germans and silencing the guns. Gerald collapsed to the ground.

He had successfully saved his comrades, but he had paid with his life. Unable to properly tally and record American dead, Gerald was originally reported as Missing in Action. His parents did not receive the news of his death until the spring of 1944. He was buried at the Sicily-Rome American Cemetery. Though his body was never to return home, his parents placed a cenotaph for him in Greenfield reading: “Greater love hath no man than this, that a man lay down his life for his friends.” He was just 30 years old.

Perhaps They Sang a Hymn

In the days following Gerald’s death, Vernon was flying missions in the Pacific. By December, he had already distinguished himself for incredible bravery, once landing his PBY Catalina “flying boat” on turbulent seas to rescue a downed pilot following a Japanese attack. For this bravery and kindness, he was beloved by his crew. On one occasion, after the death of one of their officers, “Vernon organized and trained in a few minutes a choir of men in the squadron, found somewhere an organ (creaky but resounding), and led them in singing hymns which brought tears to our eyes,” recalled Lt. Ogden, a personnel officer on Vernon’s ship.

Ogden also recalled that, despite the dangers and humid, sticky weather, Vernon was determined to keep the holiday spirit alive during Christmas 1943. “There was little around to suggest Christmas,” Ogden wrote, but Vernon nonetheless “remember[ed] every man in his crew with a gift on Christmas and [sat] and talk[ed] with them on that occasion.”

Three days later, his Christmas gifts given and his crew cheered, Vernon took off on his final mission: protecting surveillance planes over the Kwajalein Atoll while they took reconnaissance photos. When several Japanese “Zero” fighter planes emerged from the low hanging clouds, Vernon was once again given the opportunity to prove his incredible bravery.

Knowing he was part of the reconnaissance planes’ only defense, Vernon leapt into action. In that moment, he was perhaps never more alike to his daredevil friend, Darrell Lindsey. Flying a PB4Y-1 Liberator bomber, Vernon engaged and shot down two of the much faster and more agile “Zero” fighter planes before he, too, entered a deadly spin towards the clear, blue waters of the Pacific. In those last few moments, those terrifying seconds where the sky and sea blurred into one, he perhaps thought of his home, of his campus, and of the new world he would never see.

On December 28, 1943, his plane smashed into the sea and was never seen again. Somewhere, perhaps his squadron found that old, rickety organ. Perhaps they sang a hymn.

Vernon’s name is listed on the Tablets of the Missing in the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific in Honolulu. He was just 25 years old.

BVU Remembers

It’s been warmer than usual in Storm Lake this winter, and the prospects of a white Christmas seem slim, but the holiday spirit is still alive and well. It shines through in the twinkling lights that line Lake Avenue, in the shimmering trees that look out from the dining hall over the lake, in the cozy fireplaces in the forum.

All around, students are studying for finals, preparing for holiday concerts, and picking out Christmas gifts. They are rushing down the halls and pulling their coats tighter on the sidewalks of the home that Gerald and Vernon had so dreamed of returning to in the world that they so hoped would be. The world they helped save. And, somewhere—in a dorm room or the Forum or the library—that old, familiar tune is playing still.

I’ll be home for Christmas

If only in my dreams…