Reprinted with permission from The Storm Lake Times Pilot and author. Eighth story in a series.

There is a place in Papua, New Guinea called Iowa.

There has never been a formal declaration of this fact—no diplomats have held negotiations and no ribbon has been cut—but it is nonetheless true. The place is small—just a bit of land a few feet long and wide—and is entirely non-descript. In fact, there has never been anything at all to suggest that this land is Iowa except for a simple wooden sign taking the form of a small, white cross. It is difficult to know what exactly was written on the cross, when it stood there. Perhaps there were dates carved into the soft wood. Perhaps IOWA was emblazoned across the white front. Or, perhaps, there was nothing at all on this grave except for a single name: Lloyd L. McCabe.

Many Homes

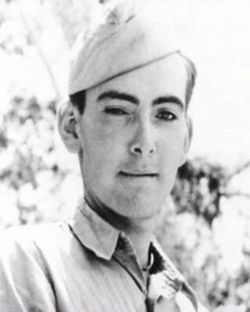

Lloyd McCabe was originally from Rapid City, South Dakota, but, following his mother’s death when he was three and his father’s subsequent illness, the McCabe children were scattered to the wind. For Lloyd, the youngest, this meant being sent to Laurens, Iowa to live with extended family. He thrived there, and, as remembered by the Laurens Sun, “always considered Laurens his home.” Following his father’s death in 1934, Laurens and the Erickson family truly became Lloyd’s world. He even informally took the last name of his adoptive family, going by Lloyd Erickson in all school activities, from plays to basketball. He was Lloyd Erickson to his friends at BVC, too.

After graduating high school in the spring of 1941, Lloyd enrolled at Buena Vista College, immediately joining the Alpha Delta Alpha fraternity and becoming fast “friends” with fellow freshman Lucy Armstrong, whom he dated for a year before The Tack reported their break-up. While at BVC, Lloyd explored his passion for acting—participating in several college plays—and found numerous friends on his new campus. Just like Laurens, Lloyd made BVC into his home. A home he would soon have to leave.

In June 1942, just a month after the end of his first year of college, Lloyd and 54 other young men from Laurens registered for Selective Service. Eight months later, Lloyd entered the service. Lloyd was sent to Camp Roberts, California, where he trained with the 145th Infantry Regiment, 37th Infantry Division. In July 1943, he was sent to the South Pacific, likely to serve as a replacement in the ongoing and costly New Georgia Campaign.

Hill 700

Following the New Georgia Campaign, Lloyd and the 145th were sent to Bougainville in November 1943. The largest in the Solomon Islands chain, Bougainville—located some 550 miles from the Papua New Guinea mainland—served as a strategic foothold against the Japanese Rabaul Air Base. The U.S. Campaign to isolate Rabaul had been going on for months by that point, and Bougainville would be the final piece in the puzzle. On November 6, the 145th Infantry Regiment came ashore and helped form part of the 62,000-man perimeter that stretched for thirteen miles across the island. The 145th was assigned to the direct center of the line, known as Hill 700.

Instead of sitting in the classroom of Professor “Bugs” Smith or attempting to rekindle his romance with Lucy, Lloyd spent the winter of 1943 and early months of 1944 in the wet, miserable humidity of the jungle, terrorized by mortar fire and boredom. The steep slopes of Hill 700—thought to be nearly impenetrable by the Japanese—were nothing like Lloyd had ever known. It must have been difficult to find any piece of Iowa or BVC, in that jungle. The foliage, the flowers, and even the dirt were different. There was no home to be found on Bougainville.

“One of My Best Buddies”

On March 8, 1944, Japanese forces attacked with the rising of the sun. Although the Americans knew an attack was coming, they were not prepared for the ferocity of the attacks against Hill 700. The steepness of the slopes made them difficult for the Japanese to climb, but also made it difficult for the 145th to see and aim. The Japanese used this cover to their advantage, and the brutal fight for Hill 700 was on. Poor weather made visibility difficult and close quarters made combat barbaric. At times, soldiers fought with knives and bayonets rather than bullets and mortars.

By dawn on March 9, the 145th had managed to hold on to their position, but the Japanese had made significant progress on the Northern slope of the hill. To prevent any further gains, Lloyd and the men of his battalion were ordered to launch a counterattack against the Northern slope. Intense mortar barrages and sniper fire slowed the counterattack to a crawl, and it quickly became a battle of inches. When night fell on Bougainville, twenty-nine Americans lay dead on Hill 700. Among them was Lloyd McCabe. “I can’t say how it happened,” wrote a fellow member of the 145th—who was also from Laurens—to Lloyd’s parents, “but don’t worry, I’ll never forget as long as I live. He was one of my best buddies.” At just twenty years old, Lloyd was the youngest Beaver to be killed in the war.

Forever Laurens

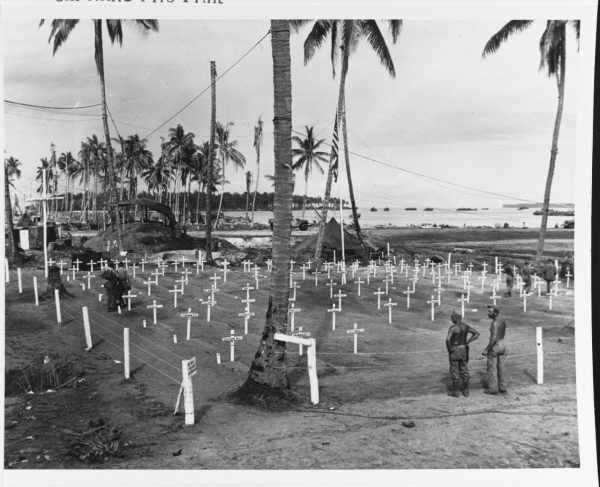

When the Japanese were finally driven back, Lloyd’s body was collected by his friends and the Company Chaplain and taken to the temporary cemetery near the village of Torokina. With full military honors, Lloyd was laid to rest. There, beneath a simple white cross and at the meeting of flesh and soil, the land was anointed. As the Laurens Sun wrote, quoting WWI Poet Rupert Brooke, “we know that there is a corner of a foreign field that is forever Laurens.”

At BVC, Lloyd’s name was published on the growing list of Beaver casualties, and President Henry Olson gave the lost Beavers a eulogy and led alumni in prayer and benediction. Somewhere, perhaps young Lucy Armstrong read the list and wept for what could have been.

With the introduction of the US Government’s Return the Dead program in 1946, Lloyd, like over 170,000 other servicemembers, was brought home. In 1948, he was buried under the name McCabe, but was interred in the Erickson family plot.

Back at Torokina, the other casualties of the battle were returned home or transferred to the Manila American Cemetery. Lloyd’s cross was removed, the soil settled back into place, and flowers bloomed at Bougainville.

BVU Remembers

Now, 81 years later, the island is quiet. The traces of war have been swallowed up by time and the rusting tanks and ammunition boxes serve as hulking, hallowed out memorials to a forgotten hill in a bygone era.

But the earth never forgets. It remembers the heat and fire of battle, the comrade from Laurens knelt next to a wooden cross, and letters from friends at BVC tucked into a jacket pocket.

It remembers that it is the small corner of the world belonging to Laurens. Belonging to Iowa. Belonging to BVU.

Finding Lloyd’s former gravesite, this piece of home, would be nearly impossible if you visited today. But, if the light was just right, perhaps you could spot it still. Perhaps you’d find, if you only looked closely enough, that those jungle flowers aren’t so unfamiliar after all. Maybe—just maybe—among the blades of grass and tangling vines, you’d find an Iowa Prairie Rose, blooming up from borrowed soil, glittering in the sun, and turned eastward, always facing the land it knows as its own.