Reprinted with permission from The Storm Lake Times Pilot and author. Ninth story in a series.

Have you ever fallen in love with a picture?

If you haven’t, take a look at Eugene Butler’s and you just might. There’s something about his features that makes him feel inexplicably familiar, something about the slight quirk of his lips that makes you almost certain you’d recognize his laughter. There’s a sweetness to his photo, a kind of softness that speaks to a gentle heart and quiet countenance. There’s a sadness, too, that aches of a life unfinished.

Model Planes and Ships

Butler’s life began in Glenwood, Minnesota, where Eugene Butler spent the first few years of his life. Sometime in the thirties, he and his family left Minnesota behind for the then-small town of Hartley, Iowa, that Eugene quickly embraced as his own. By the time he was in high school, he cut a dashing figure—six feet tall with dark hair and dark eyes—but he wasn’t partial to athletics like his stature might suggest. He enjoyed music—playing both the bass drum and timpani drum in the high school marching band—but his real love was art. More specifically, Eugene loved building model ships and planes. At 18, he had over fifty model planes and ships, which he proudly showed off to the local paper in their “Hobby Corner” segment.

Just a few months after Eugene showed off his models to the Sheldon Sun, he packed his bags and moved into the Boys Dormitory at Buena Vista College in the fall of 1942. Already, the United States was at war with Germany and Japan and pouring troops overseas, but, for Eugene, the planes and ships of war remained as models for just a little while longer.

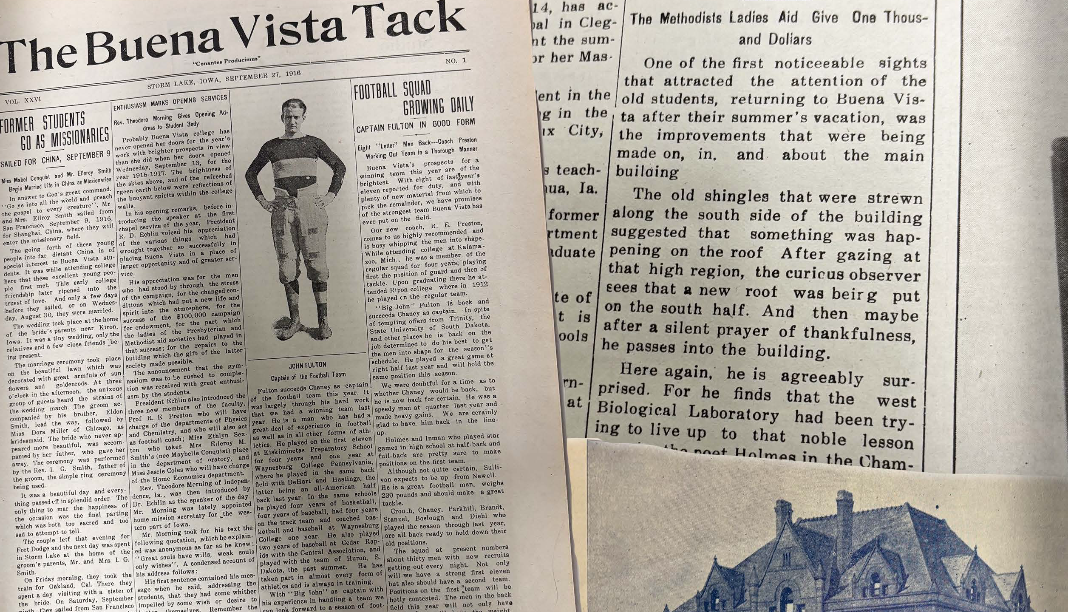

Eugene did well at BVC, but there are no records to ascertain what his major might have been. In fact, with no yearbooks published during the 1942-1943 school year, there are precious few records of Eugene’s time at BVC at all. There is no list of the activities he was a part of, but his friends called him “studious.” There are no yearbook photos, but the Tack adored him, describing him as “sedate, quiet, and gentlemanly.”

One of the Bravest

When the summer of 1943 arrived, Eugene knew it was only a matter of time before he would be called into service. Instead of returning home, he stayed in Storm Lake to work at the Gamble Store, informing the Hartley Sentinel that he was just biding his time until the draft came calling. And come calling it did. Eugene entered the service on July 7, 1943, and within a month he was stationed in San Diego California. Within nine months he was shipped overseas with the 36th Infantry Regiment, 3rd Armored Division. Sometime between Storm Lake and crossing the sea, Eugene had his service photo snapped and sent home. In it, he is still soft, still untouched by war. Still the little boy with airplanes tied to the ceiling with fishing wire. Perhaps his mother kept it on her mantle. Perhaps some friends at BVC did, too.

A thousand miles away, Eugene entered the melee in France in July of 1944. A month after the Normandy Landings, the battle for France was still far from won when Eugene and the 3rd were thrust into the bloody hedgerow campaign. As they made their way through the Falaise Pocket towards the Siegfried Line, the Third gained a stellar reputation and was dubbed the “spearhead division.”

Eugene, too, quickly gained a reputation. “When I first joined the 3rd armored spearhead outfit Gene really took me in and helped me over the ropes,” wrote his friend Stan Bauza, “…there wasn’t anything I wouldn’t do for him.” Another friend, Ralph Diana, called Eugene “one of the bravest [men] who ever went into combat.” Just as he was beloved at BVC, he was beloved by the men of the 3rd Armored. “You sure can be proud of him,” Stan wrote to Eugene’s parents.

What They Had Been Fighting Against

More than just Eugene’s parents were proud of him, Hartley and BVC were, too, both reporting with pride that he was one of the first men to set foot in Germany when the 3rd crossed the Rhine River on September 12, 1944. Following their breakthrough into Germany, Eugene spent the rest of the fall in the bloody Hurtgen Forest and the winter in the even bloodier Ardennes Forest, trying desperately to stop the German advance near the towns of St. Vith and Houffalize.

When the snow finally melted and spring crept back into the land, Eugene and the 3rd found themselves deep within Germany, at the end of a long winter and nearing the end of a long war. The fighting grew bitter and brutal as the Nazis desperately defended their homeland and the full extent of their crimes became evident.

On April 11, 1945, the 3rd Infantry Division stumbled upon the Dora-Mittelbau Concentration Camp near Nordhausen, Germany. Of the 40,000 prisoners held at Dora-Mittelbau, only 250 remained at the time of liberation. The 3rd set to work offering the medical aid they could, eventually transporting the survivors to nearby hospitals. The Spearhead Division was now a liberating division, seeing at long last exactly what they had been fighting against.

It was one of the last things Eugene would ever do.

“It Was a Hot Spot”

At just after midnight on April 15, the 3rd Armored was tasked with securing a series of towns some fifty miles outside of Nuremberg. Progress was indelibly slow, with engineers repeatedly halting the men to remove the road blockages left by the retreating German Army. Combat within the towns quickly devolved into brutal house-to-house fighting, and movement slowed to a crawl. By the mid-morning, Eugene, Stan, Ralph, and several other members of the 3rd were pinned down by German fire on the outskirts of the town of Frensdorf. Huddled behind a tank, the men took fire from every direction. “All of the men were wounded,” Ralph Diana recalled, “it was a hot spot to be in.”

As a Sergeant, Eugene tried to keep his squad organized, but, when a German rocket exploded beside them their mission changed to one of desperate evacuation. The fire was too intense for medical personnel to reach them, meaning that the men’s only hope was to stagger back to friendly lines. Knowing this, Eugene—though wounded in the back—grabbed hold of one of his more seriously wounded comrades and made a mad dash for the ambulances. By some miracle, they made it. But Eugene wasn’t done. Still bleeding profusely, he re-entered the chaos to help bring his Commanding Officer to safety. As he ran, Eugene was shot in the shoulder. Again, he made it back to friendly lines, his C.O. in tow. But this time, when he fell, he did not get back up.

On the day that Franklin Roosevelt was laid to rest in New York, Eugene Butler bled out in a sun-soaked field in southeastern Germany. He was 21 years old.

“Send Me His Picture”

In the letters they wrote to Eugene’s parents following his death, Ralph and Stan had identical requests.

“Gene was loved by all of us,” Ralph wrote , “…I would greatly appreciate it if you would send me his picture.”

“All the boys were very broken up to hear Gene died,” Stan echoed a few weeks later, “…I would very much appreciate a snapshot of Gene if you would care to send me one.”

In all likelihood, Eugene’s parents sent Stan and Ralph a photo. In all likelihood, it was the same photo pictured here. Somewhere in Germany, listening to the desperate death-rattle of the Third Reich, Eugene’s photo was tucked into the helmets or pockets or bags of his friends. Back home at BVC, it was printed in the Tack with the simple phrase: “we bow reverently to his memory.”

In Hartley, the photo on the mantle became a memorial, an epitaph to the gentleness, the college degree, and the life that could’ve been. In a closet and in boxes, model planes gathered dust. A family and a college mourned. Perhaps a dog waited by the door.

Eugene’s family eventually moved back to Minnesota and Eugene was posthumously awarded the Bronze Star in 2003.

Somewhere, in Hartley or Minnesota or the Tack, Eugene’s photo remained as a testament to love and loss. As the years passed, it cracked and faded and yellowed with age until, finally, it was tucked away in an attic or basement or archive box.

BVU Remembers . . . And You Can, Too

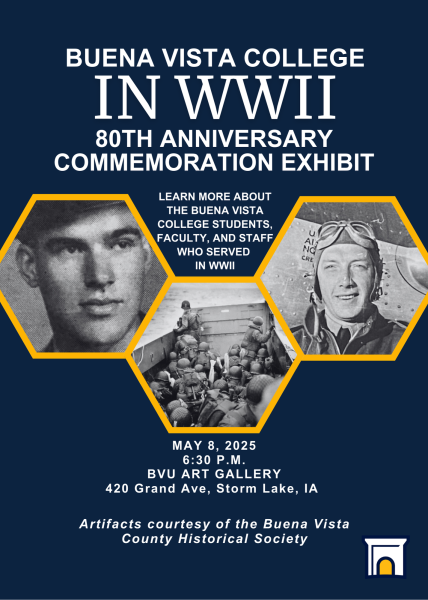

But now, 80 years after his death, his photo has returned to the Tack and the Storm Lake Times-Pilot. And, on May 8, 2025, his photo will return to the halls of BVU.

So, if somewhere along the way you’ve fallen in love with Eugene and the haunting familiarity of those striking eyes, we invite you to come visit him. Come find his picture on the wall, displayed like a photo in a yearbook that never was. Come to remember him, to memorize his features, and to learn more about BVC’s role in the war that ended 80 years ago, that day.

And, maybe, when you leave, Eugene’s photo will follow you. You’ll find him in the glittering waters of Storm Lake, in the streets of the campus he once called his own, and in the laughter that catches on the breeze that you don’t recognize, but you could swear you’ve heard before.