Reprinted with permission from The Storm Lake Times Pilot and author. Tenth story in a series.

Newspapers are a strangely liminal space. They are stuck somewhere between the past and the present, somewhere between what was and what could’ve been. Within the pages, people and moments are held in perpetuity and lives are preserved.

The newspaper is the last refuge of memory, it slows the march of history and delay time’s cruel indifference. Even so, it is inevitable that the pages will fade and wither. Someday these papers will be rendered illegible—the names unreadable—but, for now, they remain a haven for the nearly forgotten. Within the pages, people live on borrowed time.

And, every time you open the paper, you perform a resurrection. People of bygone eras linger in the headlines, their words hover in the air, and histories unspin before your eyes.

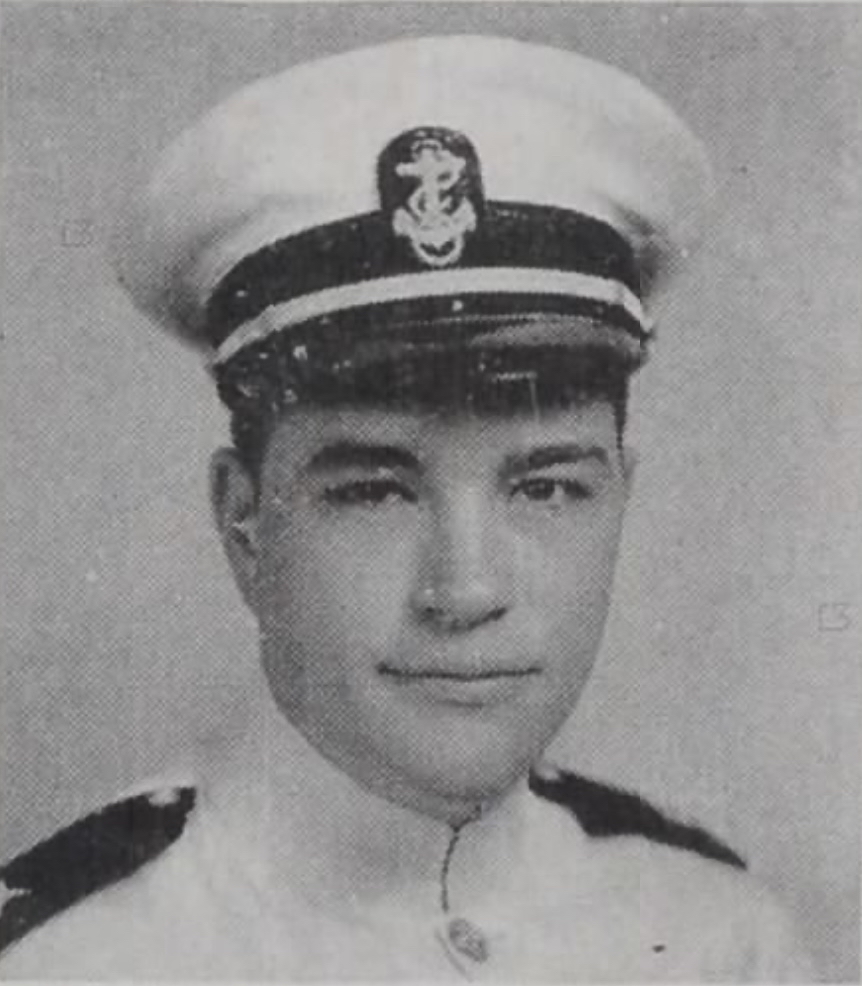

On this page, Dick Moses stares up at you. His life springs from the page. You start reading.

The story begins.

The Vibrancy of His Life

Though he was born in Sheldon, Dick Moses’ life truly began in Storm Lake. He attended both elementary and middle school there, and frequented the pages of the Storm Lake Pilot-Tribune. From his first paper-worthy solo in 1929 to his on-the-record declaration that orchestras were the best form of music, Dick appears in the Pilot-Tribune a staggering 135 times from 1930-1945.

On one page, he is dazzling audiences with his heartfelt solos. On another, he is entertaining them with his “comical stupidity” in high school plays. He is winning second place in the canoeing Regatta, he is joining the cheerleading squad at Storm Lake High, he is the only one to show up to the dance in costume.

At times, the pages read like a love story, telling of his youthful romances with Maeve Curtiss and Kathlyn Burkholder. At times, they read like an adventure novel, telling of the trip eastward in which he hitchhiked to the New York World Fair (which he proclaimed to be worth the twenty-five cents).

The vibrancy of his life spills out of every picture and his laughter dances in the margins. His heartbeat skips across the page in bold, black ink. He is ebullient and precocious. He is daring and spirited. He is stunningly, achingly alive.

When he graduated high school and enrolled at Buena Vista College, he filled the pages of the Tack just as surely as he had the Pilot Tribune. He worked on the homecoming committee, served as class secretary, and sang with the choir. He continued his “comical stupidity” in college plays and had a mysterious breakup with Kathlyn that neither the Tack nor the Pilot-Tribune ever explained.

“On Borrowed Time”

He was an ideal student, full of energy and humor and restless ambition. But it could not last. As republished by the Tack in 1942, “all [men] are acutely aware that they are in college on borrowed time…”

By the spring of his freshman year, the country was on the brink of conflict with Germany and Japan. By spring of his sophomore year, the United States was at war. Ever the adventurer, Dick enlisted in the US Army Air Corps in July 1942 with the hopes of becoming a pilot. Unfortunately, his eyesight wasn’t quite good enough for the role, but he found his way into a B-24 Liberator anyway. In March of 1943, he graduated from navigation school and became a Navigator with the 458th Heavy Bomb Group. Dick remained in the U.S. throughout the rest of 1943, but, again, was on borrowed time.

For, overseas, the US Army Air Forces were hemorrhaging men. In 1943 alone, the US 8th Air Force lost over 9,000 airmen. The average life expectancy of a crew was 11 missions, and 3 out of 4 men would be killed, captured, or wounded before reaching the designated 25 missions.

In January 1944, Dick was shipped overseas to help staunch the flow of destroyed bombers and missing airmen.

In March—just over a year since his navigation school graduation—Dick took part in his first combat mission: a bombing run over the town of Friedrichshafen, Germany. The flight was catastrophic, with poor visibility, devastating anti-aircraft fire, and dozens of Luftwaffe fighters harassing the bomber planes every step of the way. The mission cost the 8th Air Force over 400 men.

Morale was inescapably low. With crews coming and going—sometimes before their names even hit the rosters—lives seemingly became expendable. It became a matter of “when” not “if” a crew would go down.

Life Was Measured in Missions

Yet, Dick gave no indication of such feelings or of the ever-present danger tied like a noose ‘round his neck. Ever faithful, he wrote the Tack and Storm Lake Pilot-Tribune to let them know that he was “all right” even though he could see the bomb raids from his base. He imbued his letters home with liveliness that must’ve felt foreign in a place where life was measured in missions.

In the next month, Dick and his crew flew 8 missions. In the next month, the 8th Air Force lost over three thousand men.

Three thousand men killed or missing in action. Three thousand empty bunks. Three thousand telegrams.

On April 22, 1944, Dick stepped aboard his B-24 and prepared for his eleventh combat mission. With the completion of this mission, Dick could finally write home that he had beaten the odds, that he had nearly made it to the halfway point of those dreaded twenty-five missions.

The task force for this flight—Mission 311—was 800 bombers and 8,000 crewmen strong and the target was a marshalling yard just outside of Hamm, Germany. Hamm was home to a massive complex of railyards—some 630 yards wide—and was a key point of production for the German war machine. As the first raid on Hamm, this mission was considered one of critical importance.

When Dick took to the air at around 6:30 PM the night of the 22nd, dusk was already creeping across the horizon. Conditions were windy but clear. Operations declared it to be “CAVU: Clear and Visually Unlimited.” And unlimited it was. At 23,000 feet above the earth, the sky appeared to stretch on forever. Cloud cover was low and sparse, and a blue haze shrouded the land far below. At the edge of all sight—the edge of what appeared to be all things—the reds and yellows of the sunset melted into the purple twilight. The air was calm, only the hum of the engines and low radio chatter breaking the stillness of the hour. In another place and in another time, the summary of the first hour of the flight may have been intimately familiar: all quiet on the Western Front.

As night took hold, the wind picked up. It buffeted the liberators and hindered navigation. Dick’s crew had to repeatedly adjust their airspeed to make up for the formations veering into their path, and most of the 458th ended up severely off course. Through sheer force of will, Dick and his crew managed to reach Hamm. At just before 8:00 PM, the bombay doors opened, and some 2.5 tons of bombs tumbled out. Just like that, it was no longer quiet.

Brutal anti-aircraft fire exploded around the bombers and sent flak into the wings and siding. Luftwaffe and American fighters clashed fiercely. By the time the tattered formation limped home to Norwich, nearly a dozen bombers had been lost to flak and fighters.

Suspended in the Pages

Night fell quickly on the returning bombers, and the black expanse of the channel must have been a strangely welcome sight as they re-entered the Allied airspace. Having successfully navigated his crew home, Dick might’ve closed his maps and watched the channel toss and turn beneath them. He might’ve watched the last rays of sunlight sink into the earth and imagined how he would describe it to his friends back home at the Tack and Storm Lake Pilot-Tribune.

As they neared the Norwich Airbase, a sudden explosion lit up the sky and rocked the returning planes. Far below, air raid sirens wailed, and the base was plunged into darkness. The Luftwaffe had followed the bombers home. The bombers scrambled to counter the enemy, Dick and the bombardier likely rushed towards the spare guns. Perhaps Dick was frightened by the dark unknown. Perhaps he was simply thinking what a story this will make for the paper.

Another blast of fire rocketed through the air and set the wing of Dick’s plane ablaze. The plane rocked violently, the battered crew lost control, the engines screamed, and….

And, if you stop reading now, Dick Moses is still alive.

If you put down your paper and walk away, his story remains unfinished, unwritten. He is suspended in the pages, in time, and in between life and death. If I stop writing, then he is still singing solos and hitchhiking east. He is an old man and in the twilight of a long, well-lived life. Maybe he is even reading this right now.

I don’t stop writing. You don’t stop reading.

“All That Joy, All That Life”

The plane fell into a tailspin and smashed into the earth. It was so brutal that witnesses were ordered not to tell family members any details of the crash. The fire was hot and unforgiving as it burned brightly in the dark English countryside. Six of the ten crew members were killed on impact. Among them, lying somewhere in the shattered glass and twisted metal, was Dick Moses. He was 21 years old.

So the story ends.

On base, photos and trinkets were packed away and shipped out. A bunk was stripped and left empty.

Back home, the newspapers that so patiently waited for and so lovingly published tales of Dick’s adventures published a eulogy.

“We bow in sorrow,” mourned the Tack.

“We feel a sense of personal loss,” lamented the Pilot-Tribune.

All that joy, all that life, that had so faithfully filled Dick’s stories was extinguished, the embers of it dying like the fading fire of a smoldering wreck in an English field.

In Storm Lake, a tan Western Union telegram was shoved into a mailbox. The mother and father that went looking for a letter found a notice of death.

Perhaps they were surprised by the telegram. Perhaps it was as shocking and violent as the crash itself. Or, maybe they weren’t surprised at all. Maybe it felt just as inevitable as being drafted and sent overseas. Maybe it was written in the stars. Borrowed Time.

BVU Remembers on May 8

So that is all there is. It ended the exact way you knew it would. But, somehow, that didn’t stop you from reading.

In fact, it might not even stop you from reading it again, today or tomorrow, or on May 8th. May 8th, when you just might find yourself on Dick’s campus, wandering halls full of ghosts and searching for a face you know. And, amongst the posters and on the walls, you’ll find him, and you won’t think of burning planes or borrowed time. You’ll think of the Tack and Pilot-Tribune. You’ll think of “comical stupidity” and adventure novels.

You’ll start reading again, from the very beginning, and Dick will be resurrected. You know how it ends, yes, but you read anyway. You remember him.

And so the story begins again.

So please, come. Bring him to life once more.