Not an Absolute: Freedom of Speech on a Private Campus

December 5, 2018

Many regard their first amendments rights as absolutes, fundamentally protecting their right to free expression. It’s for this reason that many students of private schools are surprised to learn that as non-government entities, their institutions have no legal obligation to uphold the rights guaranteed by the first amendment.

Freedom of speech, according to a 2018 survey by the Freedom Forum Institute, is the most commonly remembered and recognized First Amendment right. As Americans, we tend to prioritize freedom of personal expression over others, aiming to support the free exchange of ideas that an effective democracy relies on. However, the line drawn between acceptable and unacceptable expressions is a murky one, and largely dependent on the perspectives and intent of the parties involved. After all, can we really say that a message should be censored or silenced simply because someone else finds the message in opposition to their own views? Particularly if the goal of the message is to change the views of others?

Examples of this conflict can frequently be seen in the disinvitation of controversial speakers. A 2016 Student Press Law Center article has found a growing movement of students “putting pressure on administrators” to disinvite speakers with perceived controversial platforms, particularly those with political connections antithetical to the majority views of the students. While both public and private campuses have experienced these events, private campuses account for 65 percent of the total number of instances. The danger with this approach is, of course, that in protecting the expression of ideas we do agree with, we risk stifling those ideas and views held by others; that such speakers were invited at all suggests a certain level of interest in hearing them speak, an interest stifled by the vocally opposed majority.

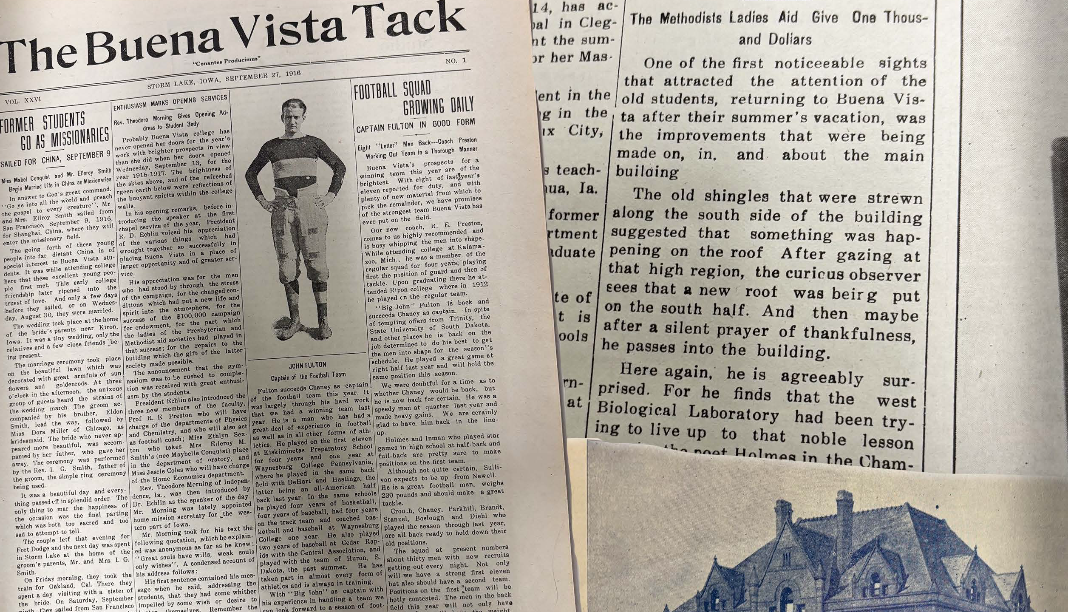

An example closer to home, as well as one showing the opposite approach, can be found in the kneeling movement last fall. Employing symbolic speech, student athletes made a statement in support of the Kaepernick movement by kneeling during the national anthem at the Homecoming football game. Outspoken responses to the incident, both positive and negative, were quickly levelled at both President Merchant and the student leaders of the protest, according to a 2017 Tack article covering the incident. While some of these responses were positive, supporting the student initiative in making a statement, others were more directly negative, ranging from criticisms of the coaches and administration in allowing the protest to threats of cancelling donations. The article further outlines the meeting between Merchant and the student leaders to reach a compromise on the matter, as well as Merchant’s intent to weigh the argument of each side before making an administrative decision.

“I listened to the students; I listened to the faculty; I listened to the community,” said Merchant, adding that, “I think it was important to create conversation, and listen to perspectives, because at the end of the day then, it [would’ve been] just my decision, and based on just me. And I don’t think that’s right.”

As a private university, Buena Vista University is not held to the same legal standard as public universities; BVU administrators are under no legal obligation to protect the freedoms of expression guaranteed under the First Amendment and hold the legal right to at any time impose restrictions on student conduct that would otherwise be seen as violations of First Amendment rights. However, what can be done is rarely the same thing as what is done.

Jamii Claiborne, a digital media professor and student expression advocate as an 18-year advisor to student presses, shares that while “At any moment the institution could limit those [freedoms] legally,” it has been her experience that BVU generally does not limit student expression without a good reason. Instead, Claiborne argues that BVU is generally a very supportive campus, and that “I think when things do happen we try, administratively, we try to have meaningful discussions with those who were involved in whatever the expression was, try to really have an engaged discussion about it.”

This can certainly be seen in Merchant’s response to the kneeling incident. While the general response was generally negative—complaints that he allowed the incident, complaints that he didn’t allow the incident, complaints that the matter took too long to resolve—Merchant’s resolve to hear all sides before making a decision reflects an effort to respect the views of every side to better reach a fair compromise.

Freedom of student expression is something we should certainly strive for, but when controversial issues are involved it can become difficult to give fair respect to multiple opposing views. I’d like to encourage a bit more tolerance for the viewpoints of others, provided that they don’t directly incite violence. A university is, at its core, meant to be a place of learning and exchanging ideas; to stifle the viewpoints of others out of preference for one’s own limits that exchange and the potential for intellectual growth.

At the same time, those planning to make use of self-expression should understand the reality of the situation. With no legal basis for free speech protection, beyond that guaranteed by school policy, much of a student’s ability to express themself is at the whim of the administration. For those who feel that their intended message would be limited by administration policy, working out of the bounds of that policy can be an option, so long as they remain aware of the potential ramifications of doing so. It’s also important to note that any message with significant meaning is likely to receive some degree of blowback; there’s no avoiding differences of opinion in life. When it’s necessary to break school policy to get a message across, or if breaking policy is in and of itself a part of the protest, Claiborne encourages being “purposeful and intentional and respectful in how you do it.”

“I think that those who do that are more likely to not be shut down . . . There’s a risk, there’s no getting around risk, but if you’re going to push on a first amendment on a private campus, you’re taking a risk, and that’s probably okay.”

For students who want to express themselves while avoiding blowback from administration, Claiborne has some more straightforward advice: “I would just encourage students to do it, to express themselves the way they wish to express themselves within the policies that exist.”

As discussed before, while BVU administration is under no legal obligation to protect the rights of student free expression, their policy has always reflected a desire to encourage the freedom of students, balancing as many competing interests as possible to come to fair conclusions. Compared to many other private schools that place more specific restrictions on student expression, BV’s policy reflects a very progressive and caring approach to student rights. Keep that in mind the next time BV administration responds to student expression.