Oppressing Student Press: The Present

December 4, 2019

“We are just trying to get out there to say,

whether or not we’re student journalists,

we are still journalists,”

– Mariah Valle

On Jan. 30, 2019 the Freedom Forum Institute, along with the Newseum and the Student Press Law Center (SPLC), declared 2019 to be the Year of the Student Journalist. The announcement aimed to recognize the important role that student journalists have and the impact they make. Marking the 50th anniversary of the 1969 U.S. Supreme Court decision in Tinker v. Des Moines Independent Community School District, which defended the free press and free speech rights of students, the Year of the Student Journalist also hoped to shed light on the challenges that they face.

In 2018, an article by the New York Times, Hard News. Angry Administration. Teenage Journalists Know What It’s Like, was published in reaction to the oppression student journalists were facing across the country for reporting on subjects like school shootings and adolescent sexuality. And that’s not all.

In California, a principal condemned the publication of an article on teenage relationships. In Utah, a student news website was shut down following the creation of an investigative piece on the dismissal of a teacher. In Texas, a principal “forbade the publication of an opinion piece critical of the administration for scheduling events during the National School Walkout protest.”

In 2019, the State of the First Amendment (SOFA) Report shared that, in understanding the American familiarity with the First Amendment, participants recalled freedom of speech most commonly (64%), with freedom of religion (29%), freedom of the press (22%), the right of assembly (12%), and the right to petition (4%) following respectively. These statistics, as well as the report as a whole, aim to shed light on the lack of awareness surrounding all five freedoms we are granted.

Honing in on freedom of the press, addressing trust in student press is seen as important in today’s current climate. Student journalists today face many different challenges.

This is evident in a recent 2019 article Illinois school district censors student newspaper. Is it a violation of the New Voices law? New Voices is a student-led grassroots movement that aims to protect student press freedom through state laws which counteract the 1988 Hazelwood v. Kuhlmeier Supreme Court decision giving schools the ability to censor information.

The article highlights an Illinois school district’s censorship of an article as well as the locking up of all print issues for a day. Student journalists said this violated their rights. The article in question showcased eyewitness accounts of the disruptions caused by a special needs student. Prior to publication, the principal cut out a quarter of the text based on the claim that the student’s privacy was infringed upon. The student was never explicitly named, nor was the situation the main purpose of the story.

According to the 2019 article, Under this New Voices law, there are only four instances in which a school administrator can use prior restraint of student expression; if the material:

- Is libelous, slanderous or obscene

- Constitutes an unwarranted invasion of privacy

- Violates federal or state law

- Incites students to commit an unlawful act, to violate policies of the school district, or to materially and substantially disrupts the orderly operation of the school.

In the college setting, Northwestern University’s coverage of protests surrounding Jeff Sessions, a former attorney general, gained intense scrutiny. A New York Times publication shared that, “student protesters were pushing through a back door of the building. The police confronted them and tried, unsuccessfully, to block their entrance. Colin Boyle, a student photographer for The Daily Northwestern, the campus newspaper, captured it all.”

Because his photos faced backlash, Boyle ended up taking them down, and The Daily Northwestern apologized for their coverage. Professional journalists immediately spoke up, commenting on the role journalists play.

Some student journalists responded by saying they “found themselves struggling to meet two dueling goals: responding to the changing expectations of the students they cover, particularly from those on the political left, while upholding widely accepted standards of journalism.”

From coast to coast, American student press is dealing with instances of low support and high curtailment.

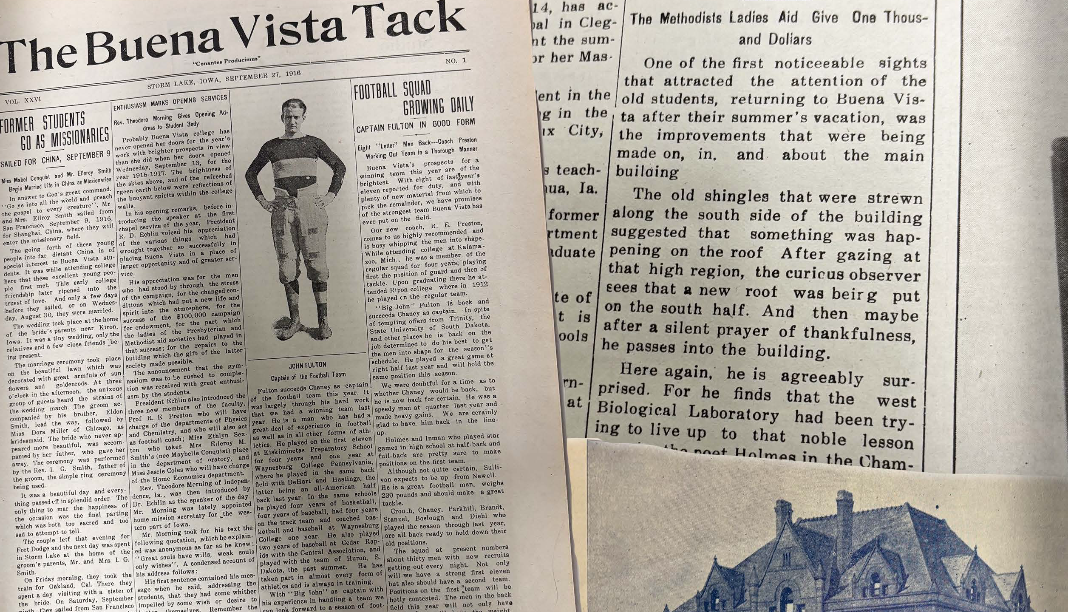

Luckily, here on the campus of Buena Vista University (BVU), student journalists haven’t experienced much in regards to censorship, at least not recently.

Allyssa Ertz, current Co-Editor-In-Chief of The Tack, BVU’s student newspaper, shared her opinion and personal exposure to censorship.

“I have not personally had an experience where I have been censored in my student press position,” said Ertz. “I think it is important that the students know the truth about what is happening around them within their University, and I feel that censorship could hinder that in the future.”

Ertz expressed that if something that could affect student life undergoes censorship, that is where journalists could run into issues. She believes that journalism is giving the public the information they deserve to know, and if student press is censored under certain circumstances, the truth is then in danger. Why? Because students are not able to hear it.

Jamii Claiborne, former advisor for The Tack and current Director of Assessment, Faculty Development & Advising at BVU, also shared that she has not been witness to any form of prior restraint in her time at the University.

Upon questioning Dr. Joshua Merchant, who is in his third year as BVU President, he shared that private schools, like BVU, have no obligation to uphold the rights guaranteed by the First Amendment.

“The kind of institution we (BVU) are has allowed our student press the freedoms, rights, and protections afforded through the first amendment even though we are not required to do so.”

While he has not been a Beaver long, Merchant shared that he tries his best to be open to meeting with the press for interviews or opinions. While the nature of his job is perhaps challenging in regards to his own personal opinion, he considers himself open and willing to meet with students.

“I think students should be allowed to post and write things that are grounded in fact and are not slanderous, hurtful, or misleading. I believe our advisors and student press at BVU has done a good job in this area.”

Here at BVU, student journalists are fortunate not to have dealt with prior restraint and censorship.

At least for now.

The future, however? Well, we’ll have to wait and see.