A Thousand Tiny Pieces

May 30, 2023

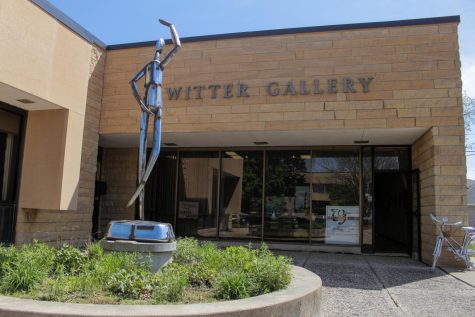

If you’d walked into Witter Gallery the week of May 15, you’d have been greeted first by sounds of pieces of tiles clinking together, occasional cracking as they were broken down, and the grinding of a metal file smoothing them out. If you then made your way towards the noise, you’d have seen two figures—one tall young man, the other a middle-aged woman—deep in focus, huddled around a folding table, working to combine a thousand tiny shards of clay tile into a mosaic of the Virgin of Guadalupe. If one of the artists happened to notice you, she’d have greeted you with a bright smile and open arms as she explained exactly what they were doing in a warm, thickly accented English. That artist is Mary Carmen Olvera Trejo (Mary Carmen to all who meet her once), and her partner in the project, Gael Uriel, two traditional Mexican mosaic artists.

How did these artists end up thousands of miles from home in small, northwestern town in Iowa? Well, to know this, we must travel to a town three hours outside Mexico City: Zacatlán. Known for its production of apples and other fruits, the city of 76,000 people was faced with an issue. The town cemetery had large cement wall erected around it to provide privacy to mourners and protect from the elements. Although a noble idea, the flat, gray monolith was somewhat of an eyesore. So, Mary Carmen, the head of tourism for Zacatlán, had to find a way to transform the wall aesthetically.

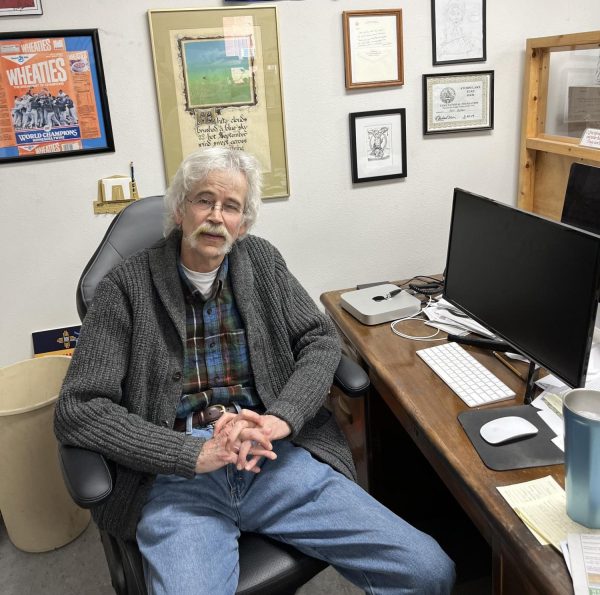

When the idea of a mosaic first came up, she was hesitant, having seen plenty of graffiti that made public spaces look even worse. However, once the project started, it was apparent that this was going to be something special. What made it special was the community investment; many hands worked to transform the Zacatlán wall. In fact, the mosaics began to draw all sorts of people to the town, including a man by the name of Dick Davis. Davis, a retired American stockbroker with a passion for the arts, met Mary Carmen and quickly realized how impactful the mosaics were for the town. He became a benefactor to the artists and encouraged outsiders to better understand the importance of community art projects like the mosaic project.

In fact, it was only by a strange twist of fate that Davis came to be in Storm Lake. He had seen and appreciated the Storm Lake documentary about Art Cullen and the Storm Lake Times Pilot. So, on his way to Chicago from California to give a lecture, he decided to stop by and see the newspaper editor himself.

Although the artists were working on a mosaic for Saint Mary’s Catholic Church, this isn’t their first project in Storm Lake. In September of 2022, the artists arrived in Storm Lake for the first time, invited by Witter Gallery to create a piece about Storm Lake. They chose the Storm Lake town sign, located at the intersection of Lake Ave. and Lakeshore Dr., adding a sunset over the lake in the background as their subject. That project was open to the public, and anyone could come in not only to watch the artists at work, but also put a piece or two down themselves.

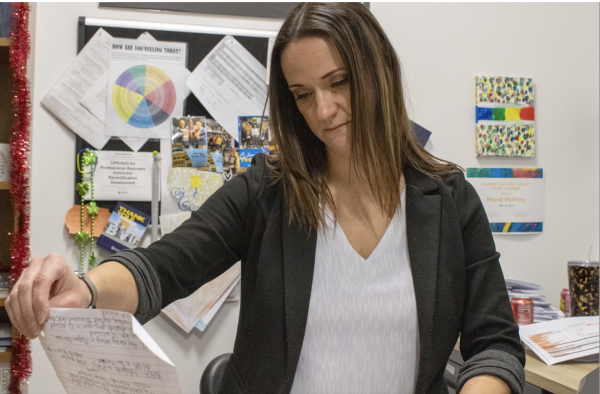

Julie Steinfeld, President of Witter Gallery’s board of directors shared her excitement, “The mosaic murals are just a little different from murals you see in other communities, and I like that. Mary Carmen came to Storm Lake last fall and shared her gifts and skills with many members of our community.”

The mosaic is different from other kinds of art for one major reason: it’s public art. Public art is defined as public art is art in any media whose form, function and meaning are created for the general public through a public process. In the case of the Zacatlán mosaic artists, the public process involves opening the process to all community members and encouraging hands-on participation, or for those a bit more shy to engage, a little education. The project is inspired by and created in part by community members. Public art also has several documented benefits, including increased sense of community. And as is the case for Zacatlán itself, such projects also have a possibility of stimulating the economy of towns they’re placed in, drawing tourism. Mary Carmen saw this in her own community, and said she hopes to bring it to Storm Lake as well.

So, after a long week of gluing, cutting, and carefully positioning tiles, Mary Carmen and Gael packed their suitcases and prepared to leave Storm Lake. The work they did, however, will continue to inspire worshippers at St. Mary’s with the striking image of the Virgin of Guadalupe. And who knows? Mary Carmen may very well return to Storm Lake and give the community another opportunity to create something beautiful. This is what she had to say: