“I see the boys of summer in their ruin

Lay the gold tithings barren…”

-Dylan Thomas

Reprinted with permission from The Storm Lake Times Pilot and author. Eleventh story in a series.

In early June, summer descends over Storm Lake in all its sticky-sweet splendor. The trees and ground explode into color and the weather warms enough for swimmers and boaters to enjoy the waters of the lake. King’s Pointe reopens, the bikers, joggers, and dog-walkers begin the awkward dance of jointly navigating the sidewalks, and someone is always mowing their lawn. Field of Dreams re-runs endlessly on TV. Save for the occasional threat of severe weather, summers in Storm Lake are nothing short of idyllic.

A Summer Untouched by Grief

The summer of 1941 was not so entirely different. Although the landscape looked different—fewer houses, fewer hotels, and definitely fewer Kwik Stars—many aspects of Iowa summers remain timeless. The boys of Buena Vista College who would soon become the soldiers, sailors, airmen, and marines of the United States Military worked in the same sprawling fields, dove into the same blue waters, and played on the same baseball diamonds.

War was already looming for the United States—its black tendrils stretching across the oceans and into the soil—but, in the quiet purple haze of an American twilight, the fighting in Europe and China seemed a million miles away. In the summer of 1941, the oft-quoted “boys of summer” were not yet in their ruin, Field of Dreams was perhaps not so far off when it asked if Iowa was heaven, and the United States was still at peace.

It was the last summer in which that could be said. It was the last summer in which BVC would be untouched by grief.

“Something Beautiful About Him”

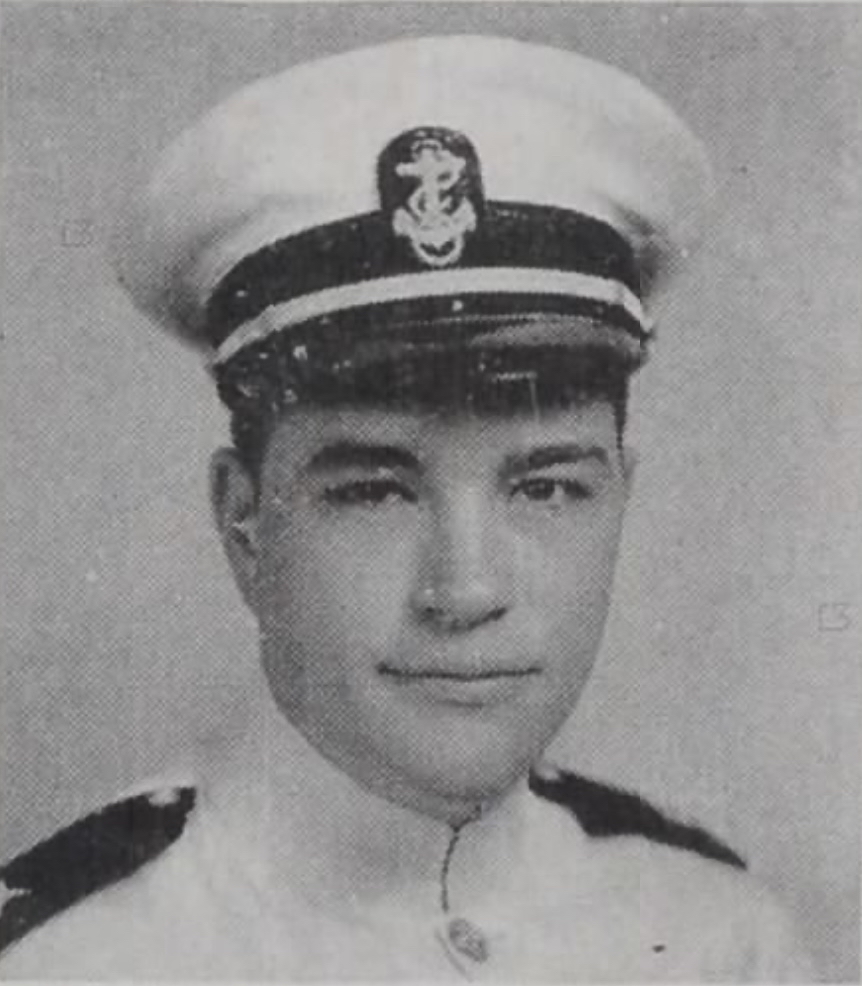

During that last, sprawling season of blue and gold and endless green, one such boy of summer who probably frequented Storm Lake was Bill Brinkman.

In the summer of 1940, Bill joked to the Tack that—as one of the only students with a car—he often found himself playing “taxi service” for his friends on campus. Though he no longer attended BVC in 1941, his “taxi service” and bright smile had earned him lasting friendships that may have pulled him homeward.

Bill was lanky—coming in at 6ft tall and weighing in at just 155 pounds—and a football and basketball star in his hometown of Pocahontas. He bounced from college to college, making friends everywhere he went. He was good-humored and quick-witted. “Of Bill one could say there was something beautiful about him,” wrote his BV friend Warren Underwood, “a quality all too rare in the lives of most people these days.”

As the dog days of August gave way to the Indian summer of September, thousands of men were drafted or enlisted into the military. The draft did not catch Bill in those fleeting days of warmth and sun, instead, he enlisted in the US Army Air Corps in the winter of 1941. Along with the other Beavers inducted into the service, Bill was quickly cycled through Camp Dodge and then moved from camp to camp across the US.

A Different Kind of “Taxi Service”

Bill spent most of 1942 training at Geiger Field, Washington, before receiving his pilot wings and his commission as a Lieutenant in September. In April of 1943, Bill was sent overseas to fly missions with the 527th Bomb Squadron, 8th Air Force.

In Europe, Bill had a very different kind of “taxi service” than he’d had at BVC. Rather than just ferrying 2 or 3 passengers, he was responsible for the lives of nine other men. Rather than dropping friends off at the Cobblestone Ballroom, he was dropping bombs at Hitler’s doorstep.

Bill’s first mission came on May 29, and was a bombing run over France. For the Eighth Air Force, 1943 was spectacularly brutal, and Bill’s “baptism of fire” was no exception. Over 150 men were killed, missing, or wounded by the end of the day. Luckily for Bill and his crew, they emerged without a scratch.

The heat of a Storm Lake summer must have seemed a million miles away. His college days were a distant memory.

Summer of Ruin

On June 11, 1943, Bill and his crew took off on their second bombing mission, this time to target the submarine pens at Wilhelmshaven. Though not deep within Germany, Wilhelmshaven was still outside the range of American P-47s, meaning that Bill and the other B-17s would be without fighters to counter the German Luftwaffe. Taking advantage of the lasting daylight of those long summer nights in June, the mission to Wilhelmshaven departed in the late afternoon with the expectation that the crews would hit their target sometime around 6:00 PM.

Bill and his crew ran into trouble some 8 miles from their target when the Luftwaffe scrambled to attack the incoming bombers. Flak, shrapnel, and fire filled the air, but Bill and his crew were miraculously unhurt. As Bill made the turn toward Wilhelmshaven, however, the cockpit was filled with the deafening screech of tearing and crumpling metal. Bill’s co-pilot—Lt. Cochran—suddenly found himself tumbling through open air and plummeting towards Earth.

The plane had been hit head-on by a German fighter, and the force of the impact had ripped Cochran from his seat and sent him through the front windshield. Upon deploying his parachute and hitting the ground, Cochran found the plane’s navigator—Lt. Homes—who had also managed to land safely after being thrown through a window. Neither man had any idea what happened to the rest of their crew, but they saw no more parachutes in the air.

Just a few miles to the West, Bill and the remainder of his crew were locked in a deadly spin. It is impossible to know what went on in the cockpit in those few, final seconds. Perhaps Bill was engaged in a frantic struggle to not only right the plane but also compensate for the loss of his co-pilot at the controls. Or, like Homes suspected, perhaps Bill and the rest of the crew were already knocked unconscious from the collision. Whatever the case, the plane and eight of her crew smashed into the ground at frightening speed.

In Oberursel, Cochran and Homes became prisoners at the Dulag-Luft POW Camp.

In Wilhelmshaven, a German field became Bill and his crew’s grave. The twisted mass of metal that had once been their plane became their headstone.

And there they remained. The boys of summer, in their ruin.

Grief Comes to Iowa

Two months later, in the dying days of the season, the August sun warmed the mailbox in Pocahontas that contained the telegram notifying Doc Brinkman of his son’s death, and Warren Underwood mourned bitterly in a letter written to the Tack. “I shall always remember Bill’s engaging smile,” he wrote his friends on campus, “[even] if I forget everything else about him.”

Bill Brinkman was just 23 years old. He was his parents’ only child.

Grief would again come to Iowa a year later as the beaches of Normandy were littered with the bodies of American youth, 15 Iowans among them. The summer after that, the fighting was in the jungles of Okinawa.

BVU Remembers the Boys of Summer

Now, 80 years after the end of World War II and 82 years after the death of Bill Brinkman, summer in the United States is peaceful.

The days are warm and filled with the sound of laughter and the crack of baseballs hitting the bat. The evenings stretch endlessly on, full of dripping ice cream cones and the smells of barbeque and woodsmoke.

Outside, children chase fireflies in the grass. Inside, parents tear up at the sight of Kevin Costner playing baseball with his father.

And, at BVU, the boys of summer have returned to their campus. For a brief moment in May 2025, their faces lined the halls and walls of the Art Gallery. Over 100 members of their community came to visit them. To honor them.

Perhaps those 100 people—and those people reading this article now—will remember Bill this summer. Perhaps they’ll picture him dancing as they dine at the Cobb and see his smile in the pieces of cotton that drift through the air like snow. Perhaps they’ll keep his memory alive. Perhaps they’ll give him what he must have so desperately wanted in those seconds before his plane hit the earth.

Yes, June has returned to Iowa.

Somewhere in Dyersville, the ghost of Shoeless Joe Jackson is playing baseball.

Somewhere in Storm Lake, the ghost of Bill Brinkman is enjoying one final summer.