Reprinted with permission from The Storm Lake Times Pilot and author. Twelfth story in a series.

Where have all the fireflies gone?

It was a question at the top of people’s minds in the summer of 1941. When the “Old Timer” column of the Storm Lake Times first posed the question, it came from a place of genuine concern. After all, fireflies were a hallmark of summer, as essential to the season as the Fourth of July and the corn that should—with any luck—be knee high. In the thirties, fireflies were so numerous in Iowa that, upon hearing that Seattle didn’t have fireflies, a Grinnell College student convinced her father—the Assistant Secretary of Agriculture—to ship 500 of them westward for the people of Seattle to see. Perhaps the ever-growing city and its lights pushed the fireflies away from Storm Lake. Or, like Andy Anderson told the Storm Lake Times shortly after, perhaps the fireflies weren’t gone at all. “I can take you out west of Alta any summer night and show you millions of ‘em,” he wrote, though no one appears to have taken him up on the offer.

While Storm Lakers missed the fireflies, some thousand miles away, Dick Brown missed everything about his little college town and dreamed of finishing his degree.

Cupid and the Journalist

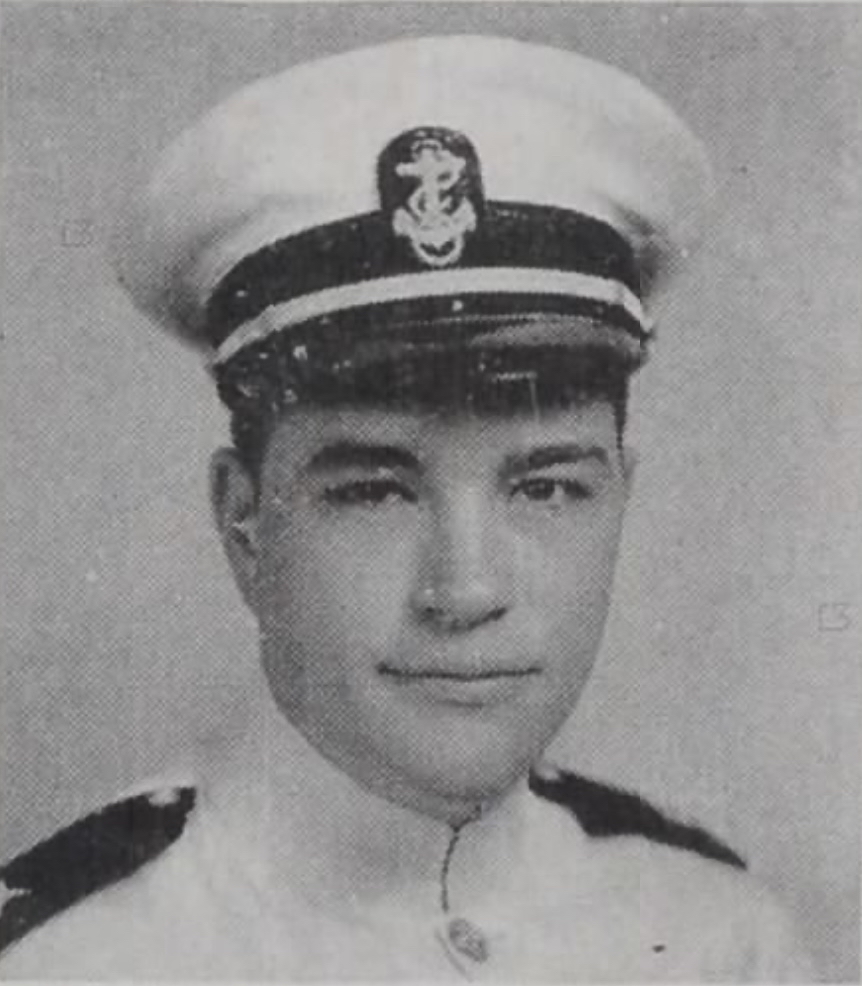

Dick, originally from Afton, began his education at Buena Vista College in 1938, studying journalism under Prof. Kermit Buntrock. Dick was a born journalist, quickly becoming business manager for the Tack, a sports reporter for the basketball team, and a loyal assistant in the Storm Lake Times advertising department. He became a part of the news almost as quickly as he reported it, earning a special reputation with the women of campus.

“Cupid strung his bow and a certain gold pin is not in its usual place…For the benefit of those who have not met him, Dick Brown has succumbed [to love] at last,” the Tack reported in June of 1938.

“When asked for news, Dick Brown said that he had a new girl, but that wasn’t news,” the Tack reported two months later.

Between the newspaper and his many girlfriends, it seems unlikely that Dick had much time to think of the fireflies, but, as a journalist, he may have noted the Grinnell incident with particular interest.

The Beaver Trio

Regardless of his thoughts on the matter, both his duties and his affections were about to change. In November 1940, Dick left BVC behind to enlist in the Naval Air Corps. For the rest of the year and most of the next, he spent his time in Pensacola, Florida, receiving advanced air training alongside his good friends and fellow Beavers Vernon Nelson and Herbert “Herb” Thayer.

“There is not much of the training here I can tell you about except that we…are doing as well as it is possible for us to do without previous military training or flying experience,” he told the Storm Lake Times, adding, “could you send me some copies of the Tack? I haven’t seen one for seven months.”

Dick was moved to Corpus Christi shortly after Pearl Harbor. There, his days as a ladies’ man came to an end when he met Miss Almabel Duecker, a local to the area. Cupid had truly got him this time. Dick and Almabel were married in February 1942, just a few weeks before Dick was sent back to Pensacola to serve as a flight instructor alongside Vernon and Herb.

Eventually, the trio were split up once more, with Dick going back to Texas, Vernon going to San Diego, and Herb heading off to Virginia. They would never see each other again.

Disappearing Fireflies

In Texas, Dick continued training pilot cadets—several of them Beavers—for warfare in the Pacific. He also welcomed a little “cadet” of his own: a daughter named Marsha, born in October 1942. Perhaps, holding his little girl in his arms, he dreamed of returning to BVC, just like he told his parents and the Storm Lake Times he would. Perhaps he dreamed of showing her the fireflies that—despite Storm Lake’s blackout restrictions—stubbornly lit the sky every summer night.

By the end of 1943, Herb Thayer was somewhere in the Pacific, Dick was preparing to be shipped out, and Vernon Nelson was dead. Just like the fireflies, the boys of BVC were disappearing.

Dick was sent to the South Pacific in February 1944 to prepare for the upcoming campaign to liberate the Mariana and Palau Islands. Almabel was expecting their second child. Dick was most certainly flying missions during those first months of 1944, but he reported none of them. Updates on his life disappeared from the papers he had once worked for.

On July 7, 1944—just a thousand miles from the site of Vernon Nelson’s fatal plunge from the sky—Dick Brown took off for a mission over the Tinian Islands. Little is known about the mission except that it ended bloody and brutally. In the Navy report, Dick’s cause of death is listed simply as “multiple extreme injuries.” He was just 24 years old.

On July 27, the Storm Lake Times reported Dick missing. In the same issue, they published an ode to July:

I sing of July, when the firefly,

His elfin lantern swings,

When locusts strum, of the frosts to come,

And many other things

Did Almabel read that paper and poem and know that Dick was gone? Did Herb Thayer know? Did the fireflies?

On August 24, Dick Brown was reported killed in action. On September 29, Richard Brown Jr. was born in Fort Worth, Texas, and named after a man he would never meet. At Buena Vista College, the golden trio had been reduced to one.

Where have all the fireflies gone?

BVU Remembers

People have been missing the fireflies again, in the last decade. Years of drought, pollution, and habitat destruction have caused a general, worldwide decline in the species, but this summer, you almost wouldn’t know it. No one really knows why the fireflies seemed to have returned this year. Maybe it’s all the rain or the temperatures. Maybe it’s something that can only be found a few miles west of Alta, in that place where locusts are humming and thoughts of frost are far away.

On campus, those little yellow lights are tinged with a special kind of nostalgia, a kind of wistful remembrance of a time long, long ago. There is an ache, to those fireflies. A memory.

In a quiet hall near the Art Gallery, a picture of Dick Brown hangs on the wall. Outside, beside the empty classrooms and weaving around the echoes of laughter long since past, the fireflies blink on.